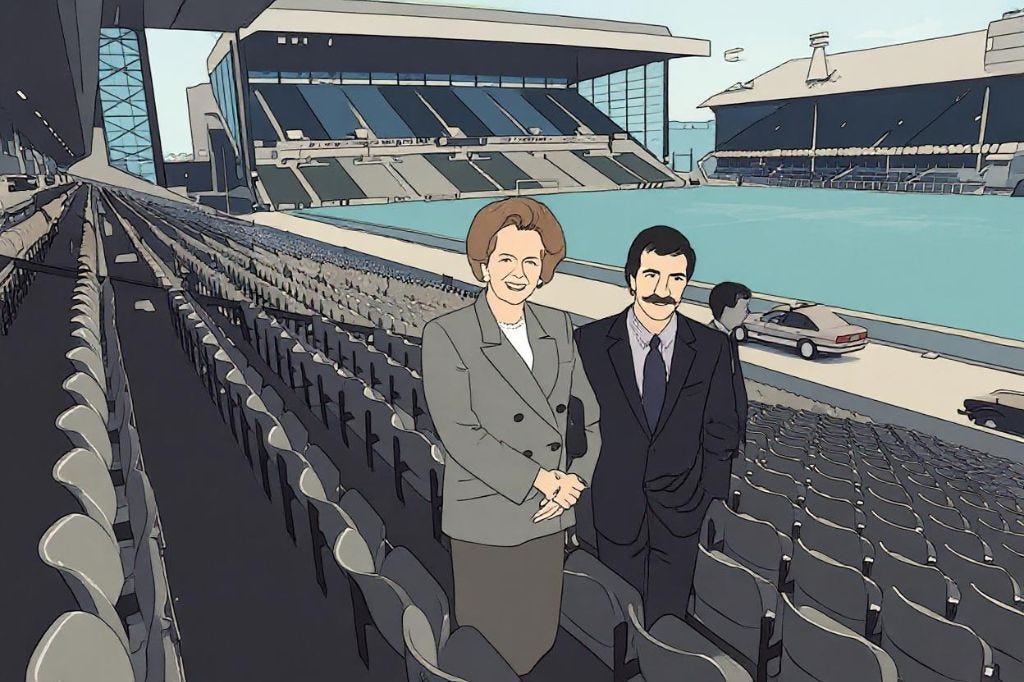

How Thatcherism changed Scottish Football Forever

Deindustrialisation, Criminalisation, and Commercialisation: Thatcher's Triple Attack on Scottish Football

Margaret Thatcher’s tenure as Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990 fundamentally reshaped Scottish football, leaving scars that remain visible today. Her government’s policies on deindustrialisation, fan treatment, stadium safety, and commercialisation transformed the game from a working-class cultural institution into an increasingly commodified product, forever altering the relationship between clubs, supporters, and communities across Scotland.

Deindustrialisation and the Death of Football Communities

Thatcherism’s assault on Scotland’s industrial heartlands devastated the communities that sustained Scottish football. The closure of steel plants, coal mines, and shipyards throughout the 1980s didn’t just destroy livelihoods - it gutted the social fabric that made football clubs cultural anchors. Motherwell’s story exemplifies this tragedy, as Ravenscraig steelworks faced systematic dismantlement under Thatcher’s government, employment plummeted from thousands to just 800 workers by 1990. The plant finally closed in 1992, making 4,500 redundant in the final two years alone.

Unemployment in the UK skyrocketed from 1.1 million at the start of Thatcher’s tenure to over three million by 1986. This economic devastation directly impacted football attendances, which had already been declining since the mid-1960s, but accelerated dramatically during the Thatcher years. The working-class communities that filled terraces every Saturday could no longer afford the luxury of regular match attendance. The three-day week, recession, and record unemployment converged with hooliganism concerns to create what one observer called a “situation beyond football’s control”.

The Criminalisation of Football Fans

Thatcher’s government viewed football supporters not as customers or community members, but as a public order problem requiring aggressive state intervention. Her attempt to impose mandatory ID cards on all football fans following the 1988 European Championships represented perhaps the most direct assault on football culture. The Football Spectators Act of 1989 would have forced supporters to register and carry computer-readable cards to gain entry to any match - a scheme that treated the entire football-going public as potential criminals.

The ID card proposal was “unjustified on free speech grounds” and “a recipe for disaster,” according to critics across the political spectrum. Nobody in football wanted it - not the referees, players, FA, Football League, clubs, or fans. Even most Conservative MPs opposed it. The plan was eventually abandoned after the Taylor report on Hillsborough raised serious concerns about fans being crushed while queuing with ID cards.

This criminalisation mindset persisted for decades. The legacy of Thatcher’s approach manifested in the SNP’s 2012 Offensive Behaviour at Football Act, which specifically targeted football fans with legislation that applied to no other sport or public activity. The act disproportionately affected young men from deprived communities - the same demographic devastated by Thatcherite deindustrialisation - giving them criminal records that “blighted their futures” for offences as minor as swearing at a police officer.

Hillsborough and the Treatment of Working-Class Supporters

The Hillsborough disaster on 15 April 1989 exposed how Thatcher’s government viewed working-class football fans with contempt and suspicion. When 96 Liverpool supporters were crushed to death due to catastrophic police failures, Thatcher’s response revealed her class prejudices. She was told by senior police officers that drunken, ticketless Liverpool fans caused the tragedy - a malicious lie.

Former Home Secretary Jack Straw accused Thatcher of fostering a “culture of impunity” for police that enabled the subsequent cover-up. The same South Yorkshire Police force that failed so catastrophically at Hillsborough had been instrumental in Thatcher’s battles against miners during the 1984-85 strike. Many believe her unwavering support for police authority prevented proper accountability for decades.

Margaret Aspinall, whose son James died at Hillsborough, stated bluntly: “She [Thatcher] presided over very dark days for football. Nowadays people going to matches are treated as human beings. But Margaret Thatcher had absolutely no feelings for football fans, for her they were the lowest people in society”. This attitude shaped policy throughout her government, treating supporters as hooligans to be controlled rather than citizens with rights.

The Taylor Report and Gentrification

While the Taylor Report following Hillsborough brought necessary safety improvements, it also accelerated football’s gentrification - a process aligned with Thatcherite market ideology. The mandatory conversion to all-seater stadiums in the top divisions by 1994 fundamentally changed the match-day experience. Standing accommodation was declared unsafe despite the report acknowledging it wasn’t “intrinsically unsafe”.

The shift to all-seater stadia drove up costs dramatically. As one expert noted, “If prices had risen on a par with inflation they’d be £16 now, not £40”. Working-class fans who created the atmosphere - were priced out. By the 2020s, Scottish football faced accusations that it had “left its working class roots and has priced itself out for the majority of the public”.

The irony is sharp, Thatcher’s market-driven policies helped create the conditions for football’s commercialisation boom in the 1990s, either through conditions allowing Rupert Murdoch to build Sky or by leaving clubs free to float on the Stock Exchange. But this boom enriched owners while alienating traditional supporters.

The Dominance of Celtic & Rangers and Structural Inequality

The Thatcher era coincided with the tightening grip of Celtic and Rangers on Scottish football, creating structural inequality that persists today. In the 1980s, the average points difference between first and fourth place was just 13 points - evidence of competitive balance. By the 1990s, as commercialisation accelerated, this ballooned to 23 points, then 37 points in the 2000s. No team outside Celtic and Rangers has won the Scottish championship since 1985.

This duopoly was reinforced by the formation of the Scottish Premier League in 1998, directly modelled on England’s breakaway Premier League. The SPL allowed top clubs to retain commercial revenues that previously had been distributed across all divisions. When the Glasgow giants engineered changes to keep all home gate receipts rather than splitting 50/50, smaller clubs lost crucial income from visits to Ibrox and Celtic Park.

The concentration of wealth in Glasgow reflected broader Thatcherite principles of market dominance and wealth accumulation at the top. Scottish football became a two-tier system: Celtic & Rangers competing (often unsuccessfully) in Europe with revenues far exceeding other Scottish clubs, and everyone else fighting for scraps.

Sky Television and Commercialisation

The commercialisation of Scottish football accelerated dramatically in the 1990s, following the English model that emerged from Thatcherite deregulation of broadcasting markets. When Sky secured Scottish football rights, it took the game off free television and forced fans to pay subscription fees. The first SPL television deal in 1998/99 was worth £11 million - up from just £3.3 million annually in 1996 - but this paled in comparison and still does to England’s Premier League billions.

By the 2020s, Scottish fans needed four separate subscription services to follow their teams - Sky Sports for SPFL matches, BT Sport for European club games, Premier Sports for domestic cups, and Viaplay for Scotland national team matches. The combined cost could exceed £90 per month [over £1,000 annually] an impossible burden for many working-class supporters already struggling with ticket prices.

This media landscape emerged directly from Thatcher’s deregulation policies. As one observer noted, “Sky fear most is football rediscovering its working-class roots, precisely because they have paid so much money to take the game away from its traditions”. Scottish football had been “burned by its proximity to the ethos that has dominated English football for two decades”.

Cultural and Political Alienation

Thatcher’s profound unpopularity in Scotland - where she was “enormously unpopular” and still to this day hated with venomous passion among most football fans - created lasting political divisions. At the 1988 Scottish Cup final at Hampden, she was loudly booed and shown red cards by Celtic fans, symbolising the broader Scottish rejection of her policies. This wasn’t just about football; it reflected how Thatcherism united “disparate parties and interests in Scotland against the Conservative and Unionist Party”.

The poll tax, introduced in Scotland a year before England as a “trail blazer,” became another flashpoint. That a million Scots refused to pay the tax by 1989 demonstrated mass resistance to Thatcherite policies. The tax contributed directly to Thatcher’s downfall in November 1990 - but only after she tried to impose it on England and riots ensued.

Football became a site of cultural resistance to Thatcherism. Scottish identity, expressed through football culture, was “largely defined by working class values” that stood in opposition to Thatcher’s individualist politics. The narrowing of Conservative appeal in Scotland during the 1980s “did not begin in this decade” but was “embedded in the working-class moral-economy interpretation of deindustrialisation since the 1950s”.

The Long-Term Legacy

Thatcherism changed Scottish football forever by severing its connection to working-class communities, commercialising the game beyond the means of traditional supporters, and creating structural inequalities that entrenched the dominance of Celtic and Rangers. The shift from communal standing terraces to individualised all-seater stadia, from affordable local entertainment to expensive subscription television packages, and from community institutions to commercial enterprises all reflect Thatcherite market ideology.

As Celtic supporters succinctly put it in recent protests against their own board: “our passion is only acceptable if it can be commodified”. This commodification - the transformation of football from cultural practice to marketable product - represents Thatcherism’s most enduring impact on Scottish football. The game survived, but it was fundamentally altered, pricing out many who built its culture while enriching those who owned it.

The working-class moral economy that once sustained Scottish football - where clubs existed as expressions of community identity rather than profit-seeking enterprises - was replaced by market logic that would have been recognisable to Thatcher herself. Today’s Scottish football, with its subscription paywalls, £30+ away tickets, and vast inequality between Celtic, Rangers and everyone else, is the game Thatcherism built.

Really powerful piece. Reading about how Thatcherism gutted those Scottish industrial towns feels close to home. The same kind of slow erosion happened in so many Irish communities when work disappeared and football lost its footing. The League of Ireland lived through that same shift, clubs trying to stay local while the world around them turned commercial.

Fantastic piece. I'd be very interested to know if Rangers fans opposed Thatcherism as vehemently as Celtic supporters. We often think of them as the ultimate 'Anglophile', right-wing club in the UK, so I wonder if they felt the brutality of Thatcherism, spiritually and philosophically, as much as others.